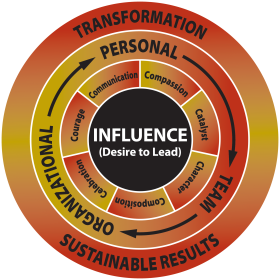

If you’ve been following along with me these past few months, then you know that together we’ve been exploring how you can discover your niche – your true purpose. To do so, I proposed that you consider three things: your strengths (things you are good at AND enjoy doing), your passions (topics, causes, people, etc. that you are deeply motivated and moved by), and finally, what other people will pay you to do.

Too often, I find that people focus solely on the financial aspect of choosing a career. They learn about what the highest paying jobs are, read lists about the fastest growing careers, pick one, and then obtain the necessary skills for it. The problem, as was previously discussed, is that skills are different than strengths. It is possible to be good or even great at something that you don’t like to do and are not motivated by. Therefore, if that is the approach you take, it is possible to end up in a career that pays well but leaves you feeling dead inside. In the famous words of Stephen Covey,

“Most people spend their whole lives climbing the ladder of success only to realize, when they get to the top, the ladder has been leaning against the wrong wall.”

For example, a few years ago, I was working in a position that I was quite skilled at but that did not align with my strengths or passions. I was in a role that was more administrative in nature: overseeing event planning and registration, scheduling coaching and training sessions, and producing and putting together training workbooks. I performed so well in my role that I was promoted to Program Director and given a 20% raise. I even had a lovely office with a view of downtown Pittsburgh. Despite all this, it wasn’t enough.

I wasn’t inspired. The work came too easily to me – I wasn’t challenged or passionate about what I was doing. I was bored. I felt myself longing for something more. I was longing for the chance to put my curriculum writing and facilitation strengths to use while investing in next generation leaders. So, I left my comfortable, well-paying, full-time job to pursue what I was passionate about – developing a leadership training program for middle school and high school girls, Blossom and Flourish.

That choice represents the only solution to the problem of climbing the wrong ladder – choosing the right wall to climb in the first place! To do so, cultivate a deep sense of personal awareness around your strengths and passions before performing an examination of financially stable careers. Instead of looking at a list of well-paying careers and choosing one to prepare for, examine your strengths and passions, and then consider how you can create value for others out of that uniqueness. In what ways do your strengths and passions equip you to offer a valuable service or product to others? What types of fields would let you pursue that?

It’s important to note that while you still might have to “pay your dues” in a few roles before you reach your “dream job,” at least you will have the satisfaction of knowing that you are working in the right field – you are climbing up the right wall. You also might have to be content with earning comparatively less than you would have in a different position or field. Less than ideal jobs or paychecks become bearable, however, if you know that they are preparing you for the next step along your life of purpose.

If we revisit my example, I can tell you that when I left my full-time job to start Blossom and Flourish, it meant that my husband and I gave up a large chunk of our disposable income. I can also tell you that we don’t regret it. We found that we were both happier with a lower combined income and the knowledge that I was working out of my purpose, than we were when I was dissatisfied five days out of the week. Even if that meant we had to give up eating out at fancy restaurants every weekend and switching from cable to Netflix.

So, what are some practical ways you can identify a purposeful career path? After understanding your strengths and passions, do your research! Thanks to the internet, the world is at our fingertips. Go on job boards and see what types of jobs are available in different fields. Join local networking groups or organizations. If you are still in college, take advantage of your career services department and ask them to help you explore the possibilities. If you aren’t already on LinkedIn, join it. Search for companies, job openings, and individuals who work in jobs you are interested in.

Then, when you meet someone who does something you’re interested in learning more about, connect with them. Message them, email them, or call them. Tell them they work in a field you are interested in and that you would love to know more about their career path and how they got to where they are today. Ask if they would be willing to meet with you and give you some advice as you pursue your career goals. In my experience, most people are impressed by that type of initiative and are flattered by such an invitation. Connecting with others like this does two things: a) it helps you learn more about a potential career path and b) it helps build your professional network.

Last fall, Karen emailed me out of the blue. She introduced herself saying that she had recently graduated from college, had an internship at a small, girl-serving non-profit, and was hoping to pursue further work in that field. She said she found my email address through Blossom & Flourish’s listing on the Girls Coalition of Southwestern PA Member Directory, and asked if we could connect. She attached her resume and cover letter.

I was so impressed with her resourcefulness that although Blossom & Flourish wasn’t currently hiring, I wanted to help her as much as I could. Long story short, we’ve met a few times now, and I’ve been able to: help her revamp her resume to better highlight her strengths, give her interviewing tips, suggest some good networking groups for her to join, and serve as a reference for her when she applied for a part-time position at another organization that I had previously worked with. She got the job. And that job has served to qualify her to apply for a new full-time position that has become available through that same organization. It all started with her initiative and a request to connect.

What Karen did, anyone can do. You just have to know what your strengths are, what you’re passionate about, and do your homework. It may take time and effort, but I promise you, it will be worth it. Certainly earning a large paycheck is nice, but is it worth ending up in a job you don’t belong in? Too many people live for the weekend and dread Monday morning. They might be earning a lot, but at what cost? Dare to be different. Dare to discover your niche and chase after it. Dare to live your life on purpose.